Sting-Sense: Bus Analytics with Inertial Sensors

This project was for a mobile computing and IoT class I took in Fall 2024, taught by Dr. Ashutosh Dhekne. 1 The goal was to build a dashboard that would allow anyone to identify Georgia Tech bus behavior across different times of the day. We were asked to collect this data by installing 2 devices on the bus – a GPS and an IMU. The GPS records the geographic coordinates of the bus on a second-by-second basis. As the bus runs its route, the IMU provides fine-grained motion data (the body’s specific force, angular rate, and orientation of the body).2 This data, we realized, tells us a lot.

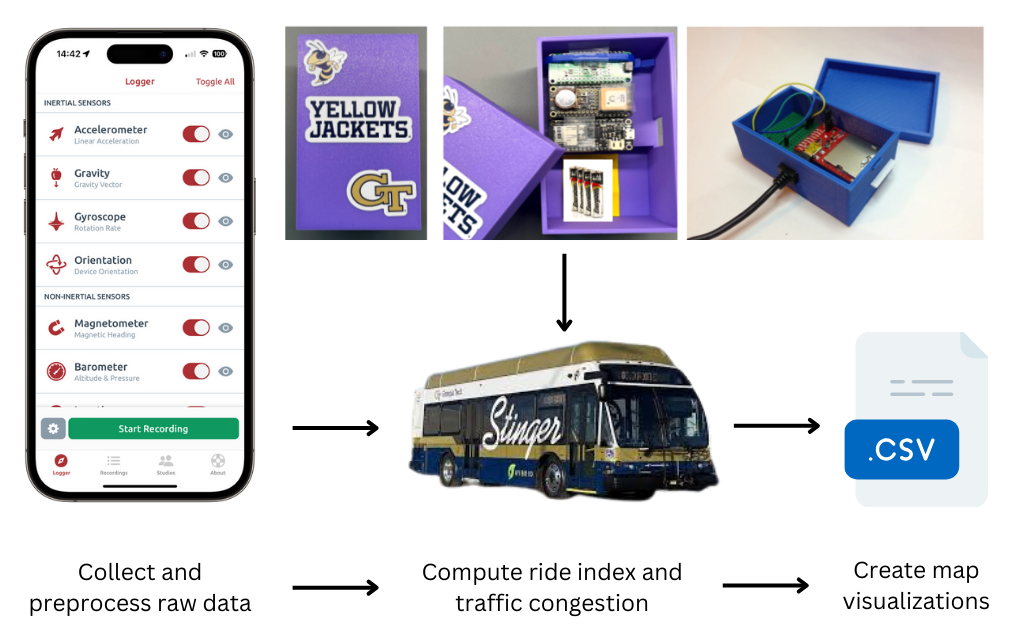

Fig. 1. Data Processing and Analysis Workflow: Using the Sensor Logger app and the hardware setup, we collect and preprocess the bus's raw raw data. Ride index and traffic congestion are computed afterwards. This feeds into the final map visualization.

A common complaint among students at Tech is the ride quality around certain parts of campus.3 The roads can be uneven, and passengers hold tight to the sides to avoid falling over. Sting-Sense made this problem more visible to the transportation department. By mapping all four routes using GPS and IMU data, we created a dashboard that tells you where the bus is bumpiest.

Doing this is not as complicated as it seems. The only major task was installing the Sensor Logger app.4 It records data from multiple sensors (more than we needed). I enabled the GPS option, in addition to the accelerometer, gravity, gyroscope, orientation, magnetometer and barometer sensors. Once I found myself on a bus ready for data collection, I stuck my phone to the wall using one of those hanging strips you find at Target.5 This keeps the phone at a stationary angle while the bus bobs around. Several metrics were logged, but the ones most useful were the:

- Local time of measurement (EST),

- Latitude and longitude,

- Accelerometer readings in three axes (x, y, z),

- Travel speed, and

- Orientation angles (roll, pitch, yaw).

The last three variables helped with inferring the road condition. The simplest solution was to use the accelerometer reading. Since the phone was stuck upright against the wall, it was the y-axis acceleration that pointed upwards.6 This would capture bumps as the bus dips into a pothole.

The y-axis acceleration was passed through a low-pass filter. This passes all signals below a predefined cutoff point and blocks anything above it.7 It helps remove any high-frequency noise, providing a cleaner signal of the bus’s vertical movement. The standard deviation of the vertical acceleration was recorded. To sound official, we called it the SDVA (Standard Deviation of Vertical Acceleration). This quantifies the variability in vertical acceleration. Higher SDVA values means more variable vertical acceleration, suggesting rougher road conditions. The SDVA was then divided by speed. Doing this is crucial because higher speeds naturally lead to more vertical acceleration, even on smooth roads. By dividing SDVA by speed, you get a measure of road roughness that’s comparable across different vehicle speeds.8

The quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3) of the normalized SDVA dataset were computed. These quartiles were used to define 5 categories of road quality:

- 5 (Excellent): normalized SDVA < Q1

- 4 (Good): Q1 <= normalized SDVA < Q2

- 3 (Fair): Q2 <= normalized SDVA < Q3

- 2 (Poor): Q3 <= normalized SDVA < (Q3 + 1.5 * IQR)

- 1 (Very Poor): normalized SDVA >= (Q3 + 1.5 * IQR),

where IQR is the Interquartile Range (Q3 – Q1).

And that’s how the dashboard below came to be.

Fig. 2. Dashboard MVP: Sting-Sense visualization. You can see all the routes mapped out, with the various colors denoting the road conditions.

This is what my professor said:

“Looks beautiful, this is exactly what I wanted. But what about data from different times of the day? This would unlock more insights, especially traffic congestion along the gold route. It’s not viable to use your smartphone anymore for this since I need data across the day. Come up with another hardware solution.”

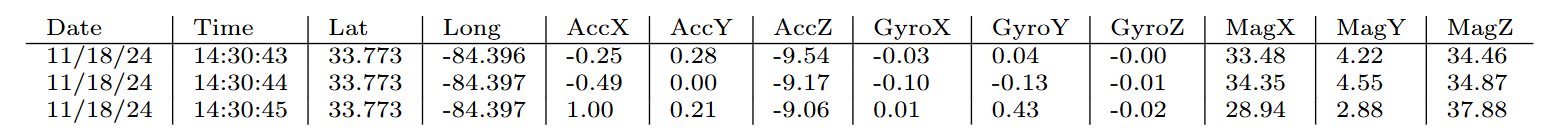

So that’s what we did. He supplied us with a microcontroller, GPS and IMU that we soldered onto a tripler - thank you to the staff at Hive Makerspace; without their guidance, setting up the hardware would have taken much longer.9 After some Arduino coding, the device spit out the following data when turned on.

2 setups were created and installed on the gold and green bus routes. We were able to collect 12 hours’ worth of data for each before the battery drained. The goal now was to infer the speed of the bus at each timestamp. Middle school math came in handy. We all know that speed equals distance over time. In the same vein, speed was calculated in the code block below:

for i in range(1, len(df)):

if pd.notna(df.loc[i, 'lati']) and pd.notna(df.loc[i-1, 'lati']):

distance = haversine_distance(df.loc[i-1, 'lati'], df.loc[i-1, 'longti'], df.loc[i, 'lati'], df.loc[i, 'longti'])

time_diff = df.loc[i, 'time_seconds'] - df.loc[i-1, 'time_seconds']

if time_diff > 0:

df.loc[i, 'speed'] = distance / time_diff # Speed in m/s

df['speed'] = df['speed'].interpolate(method='linear')

The Harversine formula is specifically designed to calculate the distance between two GPS points.10 Since the earth is spherical, this function calculates the angle between the two coordinates, using this angle to determine the distance along the Earth’s surface. Time difference is computed by converting time strings to seconds. The last two lines are where the distance over time calculation takes place, and any missing values are fixed by assuming a linear relationship between known values.

Now that we have speed data, we can use it to infer traffic congestion levels. Like how we did for road conditions, we defined 5 categories of traffic congestion:

- 5 (Heavy congestion): speed <= Q1

- 4 (Moderate-heavy congestion): Q1 < speed <= Q2

- 3 (Moderate congestion): Q2 < speed <= mean

- 2 (Light congestion): mean < speed <= Q3

- 1 (No congestion): speed > Q3

Lower numbers mean less congestion (and higher speeds), while higher numbers mean more congestion (and lower speeds). This is how we think about traffic – when there’s heavy congestion, everything slows down to a crawl.

One can gain a nuanced view of traffic conditions, not just identifying whether there is congestion, but how severe it is. However, it’s important to note that this method does not account for planned stops or traffic lights, which could be incorporated in further iterations.

The current version of this dashboard can be found here. It allows you to analyze traffic patterns for each route using an hour-based filter. We’re aware that the current version takes too long to load, compromising the user experience.

The road ahead. Improving the dashboards would be the immediate next step. Incorporating historical data and external traffic information could further enhance the congestion analysis. Furthermore, if we were to link Sting-Sense with class schedules and event calendars, we could make the bus service respond better to campus needs.11 The game-changer is when we upgrade the system with cellular network connectivity. Currently, we log bus data onto SD cards asynchronously, but with real-time data uploads to the cloud, we would make information readily available to the transportation department and the community at scale. We could make this system even more useful by using machine learning to predict when buses need maintenance. By conducting repairs before mechanical failures occur, the fleet always remains available.12

As we continue to improve Sting-Sense, Georgia Tech could set new standards for smart campus transportation and become a model for other schools and cities to follow. This project aligns with Tech’s goal of having 100% clean transportation by 2030. Leveraging IoT technologies, we can optimize route planning, monitor vehicle health in real-time, and enable demand-responsive transit services.13