Mastering Robotic Arm Manipulation with Deep Reinforcement Learning

Robotic manipulation, combining robotics and machine learning, aims to develop adaptive systems for tasks like grasping and assembling. This project applies reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms to train a robotic arm for pick-and-place operations using the PyBullet physics engine. Advantage Actor Critic (A2C), Deep-Q-Networks (DQN), and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) are evaluated and compared in terms of sample efficiency, stability, and task completion rates.

Overview. The Kuka environment in PyBullet simulates a robotic arm for pick-and-place tasks with realistic physics. It is open-source, models real-world systems, and balances complexity with tractability for RL research. This environment serves as a testbed to compare RL approaches like A2C, PPO, and DQN (value vs. policy, on vs. off policy), helping researchers choose algorithms for similar robotics tasks and inform future development.

The agent can choose from 7 discrete actions:

- Move in x-direction (+/-).

- Move in y-direction (+/-).

- Adjust vertical angle (up/down).

- Do nothing.

Velocity for each direction is equal. A height hack is leveraged, where the gripper automatically moves down for each action. As part of the reward structure, the agent receives a reward of +1 if an object is lifted above a height of 0.2 at the end of the episode. Lastly, the environment provides (48, 48, 3) RGB images as input, making way for convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to decode an optimal policy through purely visual input.1

Literature Survey

Advantage Actor Critic (A2C). Combines value-based and policy-based approaches, making it suitable for discrete and continuous action spaces.2 A2C learns a value function and a policy simultaneously, potentially leading to more stable and efficient learning in complex, high-dimensional state spaces. It employs a shared network architecture with convolutional layers feeding into separate policy and value function outputs. The inclusion of an entropy regularization term improves exploration by discouraging premature convergence to suboptimal policies.

Deep-Q-Networks (DQN). Learns control policies from high-dimensional sensory input, handling discrete policies well.3 DQN’s use of experience replay and target networks addresses stability issues in deep RL. However, its limitation to discrete actions might restrict fine-grained control needed for precise robotic manipulation. DQN tends to overestimate action values, which could lead to suboptimal policy selection.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). Balances ease of implementation, sample complexity, and performance.4 Its ability to perform multiple epochs of minibatch updates from the same trajectory makes it sample-efficient. PPO’s conservative policy update mechanism leads to more stable learning, preventing drastic changes that might be detrimental in sensitive manipulation scenarios. It uses Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE) to reduce variance in policy gradient estimates. The clipped surrogate objective provides a pessimistic estimate of the policy’s performance, potentially leading to more robust policies.

Each algorithm presents unique strengths and challenges for the Kuka arm control task. A2C offers versatility and efficient learning from visual data. DQN excels in handling discrete actions and visual inputs but may struggle with fine-grained control. PPO provides stable learning and optimization for fine-grained control, making it a strong candidate for this simulation.

Methodology. We hypothesize that PPO will excel due to its effectiveness in high-dimensional continuous action spaces (H1), while DQN may struggle with fine-grained control (H2), and A2C might underperform due to its synchronous nature (H3). The algorithms are evaluated based on: (a) sample efficiency: measured by learning speed and performance relative to training steps; (b) stability: assessed through consistency in policy improvements and value estimations; (c) task completion rates: determined by successful object manipulations in the Kuka environment. This comparative approach allows us to identify the strengths and weaknesses of each algorithm in the context of robotic manipulation tasks.

Algorithm Implementation

Actor-Critic (A2C). A2C combines policy gradient and value-based learning, making it suitable for continuous action spaces. The framework consists of an actor that learns the policy $ \pi(a \mid s; \theta) $ to select actions based on the current state and a critic, which estimates the value function $ V(s; w) $ to evaluate the quality of states and actions. The actor and critic networks share a convolutional backbone for feature extraction, with separate heads for policy prediction and value estimation.

The A2C training process involves four key steps. First, the agent collects experience by interacting with parallelized environment instances, gathering state, action, and reward trajectories. Next, advantages $ A(s, a) $ are calculated using the Temporal Difference (TD) error:

$$\ A(s, a) = r + \gamma V(s’) - V(s) $$ where $ r $ is the immediate reward, $ \gamma $ is the discount factor, and $ V(s’) $ and $ V(s) $ are the values of the next and current states, respectively. The actor network is then updated using the policy gradient:

$$\ \nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi(a \mid s; \theta) A(s, a) \right] $$ which maximizes the advantage-weighted log probability of actions. Finally, the critic network is updated by minimizing the mean squared error between its value predictions and the TD target:

$$\ L_{critic}(w) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \left( V(s; w) - (r + \gamma V(s’; w)) \right)^2 \right] $$ Deep-Q-Network (DQN). DQN implements Q-learning with deep neural networks, handling complex state spaces through experience replay and target networks. The network approximates Q-values for each action, with three convolutional layers for feature extraction from image inputs.

The DQN training process consists of four main components. It begins by sampling batches from a replay memory, which stores experiences as state, action, reward, and next state tuples. This approach breaks correlations between consecutive experiences, enhancing training stability.

A target network is employed to stabilize training by providing fixed Q-value targets, computed as:

$$\ y_i = r_i + \gamma \max_{a’} Q_{\text{target}}(s’_i, a’; \theta^-) $$ An epsilon-greedy policy balances exploration and exploitation by probabilistically choosing between random actions and those with the highest Q-value.

Finally, the model is optimized using gradient descent with Huber loss, defined as:

$$\ \delta = Q(s, a) - \left( r + \gamma \max_{a’} Q(s’, a’) \right) $$ This combines the benefits of mean squared error and mean absolute error for stable optimization.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). PPO combines policy gradients and value-based learning, using two neural networks for policy and value estimation. The network architecture comprises separate policy and value networks that process resized and normalized image frames into tensors.

The PPO training loop encompasses four essential steps. Initially, the agent interacts with the environment to collect trajectories of states, actions, and rewards. Advantages are then computed using Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE) to balance bias and variance in policy gradient estimates.

The policy network is updated using a clipped objective function:

$$\ L_{\text{clip}}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_t \left[ \min \left( r_t(\theta) , \text{clip}(r_t(\theta), 1 \pm \epsilon)\right) \hat{A}_t \right] $$ where

$$\ r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t \mid s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a_t \mid s_t)} $$ is the probability ratio, $ \hat{A}_t $ is the advantage, and $ \epsilon $ controls the clipping range.

Lastly, the value network is trained by minimizing the mean squared error between predicted and actual state values:

$$\ L_{\text{value}} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \left( V_\theta(s_i) - R_i \right)^2 $$ where $ V_\theta(s_i) $ is the estimated value, and $ R_i $ is the actual return from the environment.

Experiments

We conducted a series of experiments to evaluate the performance of A2C, DQN, and PPO algorithms within the Kuka robotic arm simulation environment. Our experiments were designed to test the three aforementioned hypotheses.

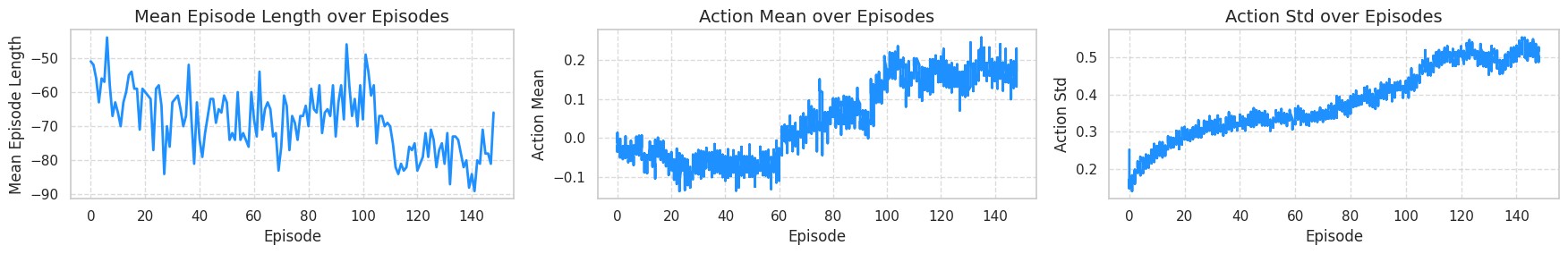

Actor-Critic (A2C). A2C’s performance partially contradicts H3. While its synchronous nature might slow learning, it demonstrates stable convergence. The decreasing mean episode length (Fig. 2a) indicates efficient task completion. The stabilizing action mean (Fig. 2b) and action standard deviation (Fig. 2c) suggest a balance between exploration and exploitation, crucial for complex manipulation tasks.

Fig. 1. A2C Performance Metrics: Mean episode length shows initial decrease and stabilization, indicating policy convergence. Action mean increases and stabilizes, suggesting the policy is focusing on optimal actions. Action standard deviation shows initial exploration followed by a balance between exploration and exploitation.

The low value error (Fig. 3a) indicates an accurate critic, while the stable gradient norm (Fig. 3b) and clip loss (Fig. 3c) suggest robust policy updates. These metrics demonstrate A2C’s ability to learn effectively in the high-dimensional space, contrary to our initial hypothesis.

Fig. 2. A2C Training Diagnostics: Value error shows consistent low error, indicating a well-trained critic. Gradient norm displays stability with occasional spikes, reflecting major policy updates. Clip loss fluctuations indicate a balance between policy retention and adaptation.

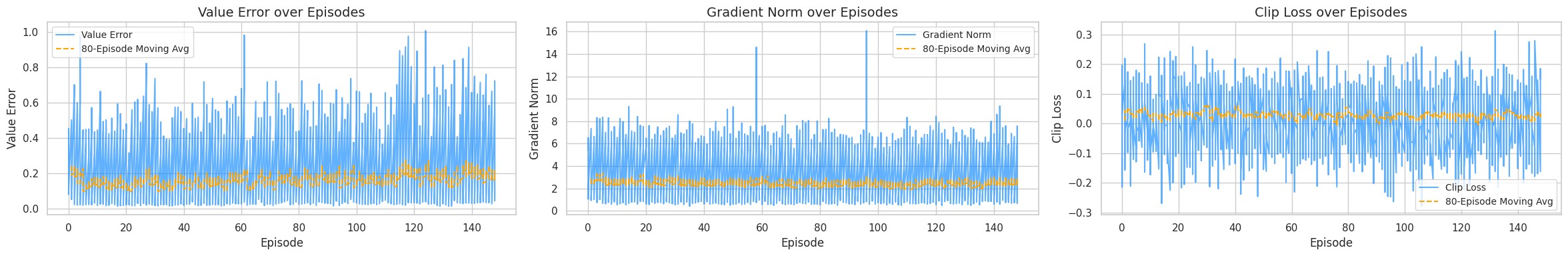

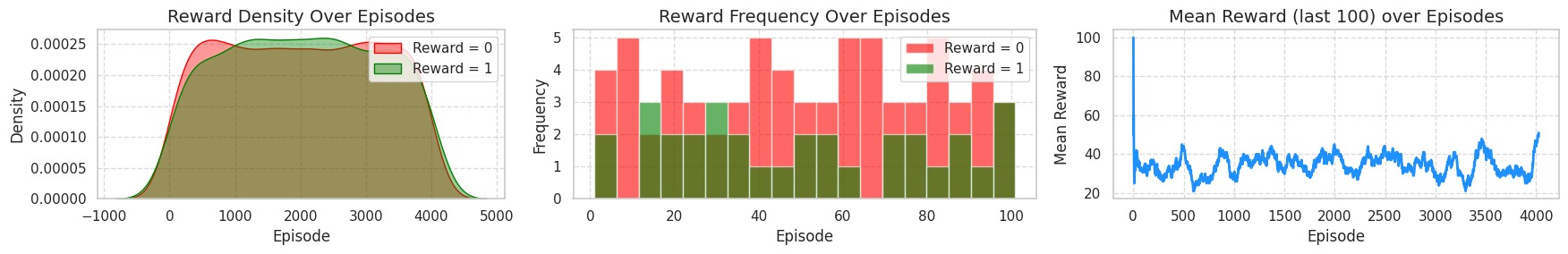

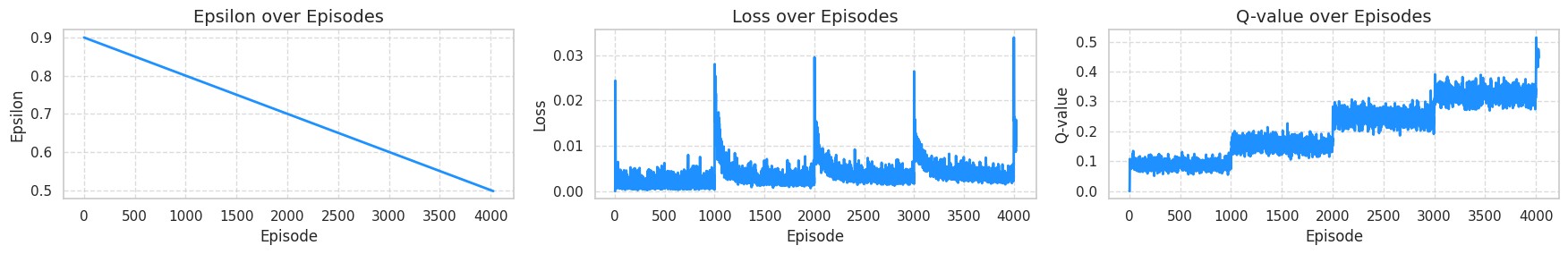

Deep-Q-Network (DQN). When analyzing the performance of DQN, we observe that overall learning progresses slowly and gradually over episodes. Specifically, the reward density over episodes (Fig. 4a) values for rewards 0 and 1 are relatively equally distributed and balanced. It measures how concentrated rewards are over episodes, providing insight into the distribution of rewards throughout training. We also measure reward frequency over episodes (Fig. 4b) and mean reward over episodes (Fig. 4c), which further illustrate the learning progress of DQN. Reward frequency tracks how often each reward value is received during an episode. Our results indicate that these values remain relatively consistent over episodes, although slightly higher rewards tend to occur as training progresses. On the other hand, mean reward over episodes reflects the average reward obtained by the agent per episode. This metric indicates stalled and gradual learning, as values plateau with occasional minor fluctuations.

Fig. 3. DQN Performance Metrics: Reward density shows balanced distribution between rewards 0 and 1. Reward frequency remains consistent with slight improvement over time. Mean reward indicates gradual learning with occasional plateaus.

DQN’s performance aligns with H2. The balanced reward density (Fig. 5a) and consistent reward frequency (Fig. 5b) suggest difficulty in achieving fine-grained control. The gradual increase in mean reward (Fig. 5c) indicates slow learning progress, further supporting our hypothesis. The epsilon decay (Fig. 6a) shows reduced exploration over time, potentially limiting fine-grained control learning. Periodic spikes in loss values (Fig. 6b) and fluctuations in Q-values (Fig. 6c) further support H2, indicating DQN’s struggle with precise control in this high-dimensional task.

Fig. 4. DQN Training Diagnostics: Epsilon decay shows reduced exploration over time. Loss values display periodic spikes, indicating instability. Q-value increases steadily with fluctuations, reflecting ongoing learning and occasional instability.

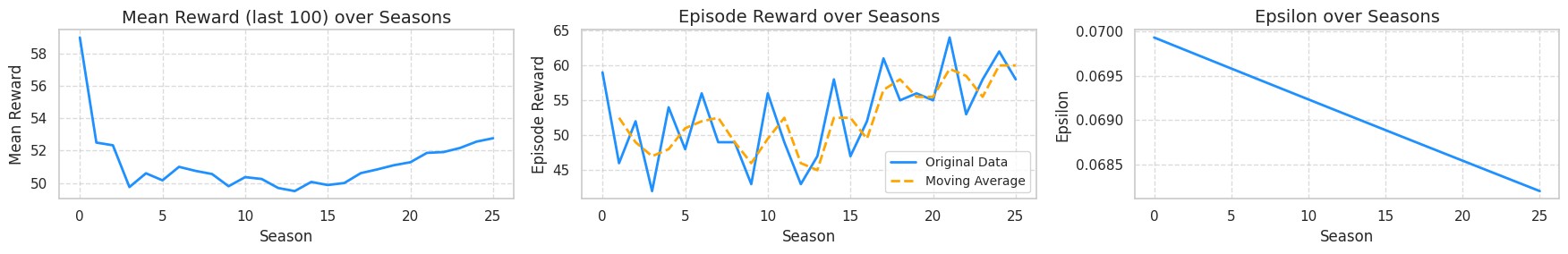

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). The following figures illustrate key performance metrics collected during training of the PPO agent in the Kuka environment. These metrics provide insights into both the learning dynamics and the agent’s evolving decision-making strategy: mean reward over seasons (Fig. 6a) acts as a high-level indicator of the agent’s overall performance. Initially, mean reward decreases, which could be attributed to exploratory behavior. Over time, the mean reward recovers and trends upward as the policy becomes more stable and optimized. Episode reward over seasons (Fig. 6b) offers a closer look at the agent’s immediate performance during specific tasks. The steady improvement in episode reward highlights the agent’s progress in task execution as it learns effective strategies. Epsilon over seasons (Fig. 6c) reflects the exploration-exploitation tradeoff, governed by an epsilon-greedy strategy. The graph shows an arithmetic decay in exploration over time, illustrating how the agent transitions from exploratory actions to exploiting its learned policy.

Fig. 5. PPO Performance Metrics: Mean reward shows initial decrease followed by consistent improvement, indicating effective learning. Episode reward demonstrates steady improvement in task execution. Epsilon decay illustrates the transition from exploration to exploitation.

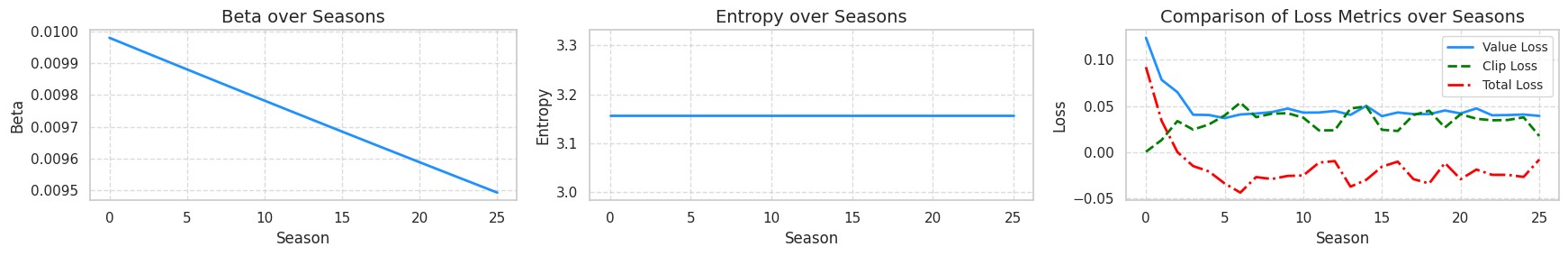

PPO’s performance strongly supports H1. The consistent improvement in mean reward (Fig. 7a) and episode reward (Fig. 7b) demonstrates effective learning in the high-dimensional space. The epsilon decay (Fig. 7c) shows a smooth transition from exploration to exploitation, crucial for mastering fine-grained control. The decreasing beta (Fig. 8a) and high entropy (Fig. 8b) indicate PPO’s ability to maintain exploration while refining its policy. The decreasing total loss (Fig. 8c) further supports H1, showing PPO’s effectiveness in learning complex control policies.

Fig. 6. PPO Training Diagnostics: Beta decay indicates increasing policy confidence. High entropy suggests ongoing exploration. Decreasing total loss demonstrates overall improvement in performance and policy stability.

Discussion

Our experiments largely support our initial hypotheses.

PPO demonstrated superior performance, excelling in the high-dimensional continuous action space of the Kuka environment. Its ability to maintain a balance between exploration and exploitation, as evidenced by the entropy and beta metrics, allowed it to learn fine-grained control policies effectively.

While showing gradual improvement, DQN struggled with fine-grained control as predicted. The balanced reward density and slow increase in mean reward suggest difficulty in consistently achieving high-reward states, likely due to the limitations of discrete action spaces in a task requiring precise control.

Contrary to our initial hypothesis, A2C performed better than expected. While its synchronous nature might have slowed initial learning, it demonstrated stable convergence and effective policy learning. The balance between exploration and exploitation, as shown by the action mean and standard deviation, allowed A2C to perform well in this complex task. Its unexpected performance highlights the importance of empirical testing, as theoretical predictions may not always align with practical outcomes in complex environments like robotic manipulation.

Conclusion. In conclusion, this work contributes to the growing body of knowledge on reinforcement learning for robotic manipulation while addressing key challenges such as efficient learning, generalization, and reliable evaluation. These findings not only advance our understanding of existing methods but also offer guidance for future research aimed at creating more efficient, adaptable, and robust RL solutions for real-world robotics.